Language Arts with Lyn Stone (St Monica's Wodonga)

Orthographic Mapping

“On Planet Multicueing, they don’t know about orthographic mapping.”

Alison Clarke, (2019)

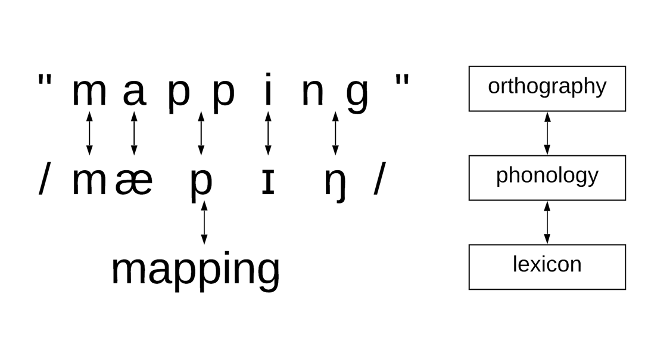

ortho (correct, straight) + graph (that which is written)

+ mapping (matching one representation to another)

How do children become fluent readers and writers? They do so by building up a store of words they can recognize effortlessly, without sounding them out and without looking elsewhere for cues. In fact, once they have a word in their sight word vocabulary, they cannot suppress its sound and possible meanings when they come to that word again.

This is the most useful meaning of the phrase sight word. There are some who define sight words as words which do not follow simple phoneme-grapheme correspondence rules. Words like eye and could, would, should etc. might fall into this category. However, this type of word is better described as irregular.

Irregular words are only classified as irregular until their structure has been analysed and explained. All words are spelled the way they are for a reason. Unfamiliar spellings only seem irregular.

Another common but inaccurate definition of sight words is words which need to be learned by looking at the whole word and memorizing it as a whole. This look-say method of teaching reading grew like a noxious weed in education in the last century. It was based on the erroneous assumption that storage and retrieval of words is an act of visual memory. It is not. Our eyes are the first processors when encountering words, that is true, but research has shown that word storage and retrieval are not functions of the visual system (Kilpatrick 2015). A blind person would not be able to learn to read if vision were the key driver in word learning.

In actual fact, it is the hearing-impaired population that gets the raw deal when learning to read, since so much of the early foundations for literacy are laid using the auditory, not visual, system.

Irregular or not, how are words memorised in the first place? Think about the massive amount of words and word parts you recognise instantly. Did you consciously memorise every single word you ever encountered? Let’s place it into perspective: the average literate adult can automatically recognise between 30,000 and 70,000 words and word parts (Kilpatrick 2016). Did we do some kind of memorization trick 70,000 times? Did someone teach us every single one? No, that would be impossible.

What we did was use orthographic mapping and self-teaching to gain our permanent sight word vocabulary.

Linnea Ehri, a researcher at the University of California, spent much of her time focusing on this process and coined the term orthographic mapping.

When learning to read, children need to be taught to look at the sequence of letters on the page, translate them into possible phonemes that they represent, and then blend those phonemes to form pronunciations of whole words.

So they map the symbols, to the sounds, to the words. The letter represents the sound which in conjunction with the other letters and sounds, represents the word. These sequences then become bonded, eventually resulting in effortless decoding, regardless of how complex the pattern is. So a word like straight can be stored just as efficiently as cat, if the person has highly developed orthographic mapping skills.

Ehri’s key findings

- Children who have good knowledge of grapheme-phoneme correspondences can retain words in their long term memory with more efficiency than those who don’t.

- Underpinning this proficiency is phonemic awareness.

- The crucial part of this kind of memorization is attention to the sequence of letters in a word.

- This builds cumulatively and eventually results in seemingly effortless decoding of familiar, and more importantly, unfamiliar or irregular words. This is where Share’s Self-Teaching Hypothesis comes in.

Share’s Self-Teaching Hypothesis

There comes a point in a student’s life that I call the sweet spot. It’s where, after sometimes many hours, weeks or months of seemingly endless effort, they begin to read unfamiliar words without them being explicitly taught.

According to psychologist and researcher David L. Share, students with sufficient phonological awareness and phonics knowledge begin to apply those skills to novel words and start to independently bond those sequences into long term memory (phonological recoding).

The important point is that again, the process involves phonological recoding. It cannot take place without attention to phonology, conscious or not.

It stands to reason, then, that acquisition of novel words, and eventually of literacy overall relies on taking that phonological route. Guessing, skipping, looking at pictures or memorizing whole words on flashcards interferes with this process. It is especially disastrous for spelling.

Some ideas for teaching to enhance orthographic mapping

Think carefully about your grouping technique

Group words to be learned as a spelling focus into close, logical families.

This can be done along orthographic, etymological or morphological lines (and those lines often overlap). Be careful though, when attempting to group words along phonetic lines. Grouping them by sound alone is inefficient, given that there can be multiple spellings for one sound.

Words are spelled the way they are because of where they came from and which families they belong to. Grouping by sound essentially ignores all of that rich, generalizable information.

In terms of cognitive load, lists containing multiple spellings place far too much pressure on working memory. A successful system for learning spelling is one which pays attention to cognitive load and pace.

Here is an example of a word list, grouped by sound, that violates all the principles of cognitive load, explicit instruction and a systematic approach:

An example of very low quality spelling instruction

Trying to teach spelling this way is like trying to teach biology by saying, ‘Let’s memorize all the things with legs.’

The unfortunate child who was given the list above, to cram for a Friday test, was asked to memorize words in the first section. The children in his class who weren’t particularly struggling with spelling were asked to memorise the middle words. The words in the last section were for the efficient mappers only. No definitions, no structure, no morphology, nothing. And the teacher would happily say she was ‘doing phonics’, not because she was a bad teacher, but because her teaching degree placed no importance on the structure of language and failed to come into the 21st century in terms of reading science.

Close families, related by more than just their sounds will win every time.

Don’t discount copying

Develop your students’ ability to copy efficiently. Copying words, sentences and paragraphs is a great way not only to practise fluency and spelling, using a scaffolded, stable framework, but if used purposefully, can also enhance everything else that constitutes writing.

Establish productive practice routines

Drill new words, first by sounding each phoneme whilst following the sequence of the letters, and then by saying the whole word.

Please don’t ask students to write the words over and over again. Anyone who has ever had the punishment of writing lines knows that after a few repetitions, those words become scratches on a page and lose all their meaning.

There is also the distinct possibility of error reinforcement, if the original word was transcribed wrongly.

To map words efficiently, students have to attend to their pronunciation in combination with the sequence of letters in the word.

Interleaving the target words throughout your teaching sequence also leads to efficient mapping. Use the words in copied/dictated sentences and paragraphs.

Have students compose sentences and paragraphs containing the words. Review all the words regularly. Break the habit of issuing on Monday and testing on Friday, never to be looked at again.

Meaning is key

Define and use each word in a sentence when teaching them. If you don’t provide definitions, the words might as well be in Swahili or Dothraki. How will students develop their awareness of the writing system otherwise? Words are related to one another and those relationships are driven by meaning. Divorce words from their definitions and you also sever the path to the full richness of the writing system.

How low quality literacy instruction leads to poor spelling

Due to the fact that letters in words appear in sequences, any instructional method that takes attention away from the sequences will interfere with efficient orthographic mapping. Some widely used examples are:

- Students are sometimes encouraged to guess words by looking away from unfamiliar words, especially if they are prompted to look at pictures instead of the word. Looking at the letters in the words in the correct sequence is not only the habit of good readers, but is the process that creates good spellers.

- Students are often encouraged to develop the habit of skipping unfamiliar words: No analysis leads to no memory.

- Students are often encouraged to only look at the first letter of a word: Partial analysis leads to partial recall.

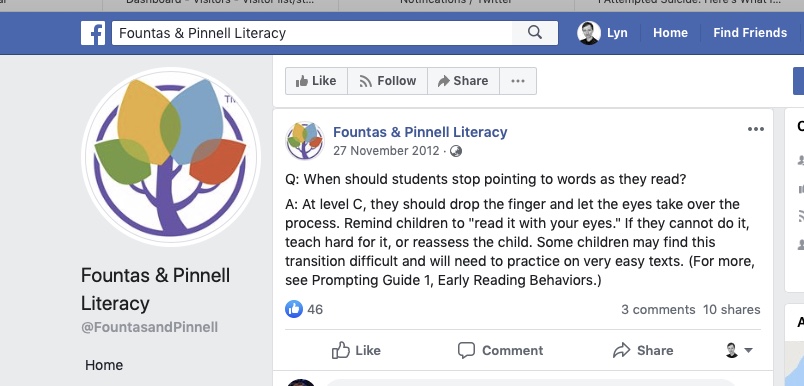

- There are some teaching frameworks that make a big deal of asking students not to point to words as they read. This is horrible. As a literate adult, I still point to words on the page if I want to read them very carefully (think legal documents and complex instructions). Taking that support away from children is ludicrous and based on zero research.

Extract from an official Fountas and Pinnell Facebook forum. Why? Just why?

- In the initial stages: providing reading material that doesn’t match the sequence of grapheme-phoneme correspondences being introduced also impairs orthographic mapping. How do children get exposure to what you’ve taught if the practice material contains other patterns?

The techniques above are the hallmark of a balanced literacy classroom. Even those children who do learn to read despite the low quality of the instruction still stand to lose vital orthographic mapping opportunities every time their eyes leave a word in search of other so-called ‘cues’.

The Language Arts approach seeks to enhance orthographic mapping at every opportunity for every child.

References

Ehri, Linnea C. (2014). Orthographic Mapping in the Acquisition of Sight Word Reading, Spelling, Memory, and Vocabulary Learning. Scientific Studies of Reading.

Kilpatrick, D. (2015). Essentials of assessing, preventing, and overcoming reading difficulties. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

For a longer explainer on orthographic mapping, click on the video below.

"*" indicates required fields

"*" indicates required fields

Orthographic mapping collaboration

Lyn Stone

Share any techniques you use to enhance orthographic mapping in your practice