Coming up to the third anniversary of the death of my firstborn, I can’t say she’s not on my mind. The anniversary effect started a lot earlier this year, with reminders just about everywhere, turning my thoughts to her, and especially to her last weeks: a kid in a wheelchair, a hospital scene on a TV show, an ambulance speeding past.

Always one to look at the positives, I’ve decided to bring thoughts of her right up to the front of my mind by, of course, writing something. It’s about well-meaning campaigns to improve the teaching of reading that use absolutes in their slogans. You may have seen them:

“Every child a reader”

“100% literacy”

“All children can read”

Can I please remind you of something? Not every child will learn to read. Even in the most advantageous circumstances, not every child will learn to read.

Take my Chloe, for example. Let’s list her educational advantages:

- white

- middle class

- read to from birth

- literate parents

- curious

- determined

- emotionally stable

- free from trauma

- well fed/cared for/sheltered

- daughter of an educational linguist

That’s a winning formula right there. Just about every positive factor you can think of in the psychosocial lottery was present. And yet she didn’t learn to read. Of course she didn’t learn to read. She was profoundly physically and intellectually disabled.

Out of all the kids in the specialist school she went to, there was maybe one kid with higher needs than Chloe. I’ve written about her a couple of times in this blog already, so if you want to find out more about her, you can, but back to the subject at hand.

Firstly, when I realised how profound her disabilities were, I didn’t give up. I did everything I could possibly do to try to teach her how to walk talk, read and write. One day I’ll write a whole book about all of it, but suffice to say, no stone was left unturned.

But there did come a point where I ceased literacy instruction. There did come a point where I knew my time and effort were not well spent there and could and should be diverted towards the development of other, more productive, useful skills for her. Hours were poured in to teaching her to use a spoon so that she could at least feed herself. Setting her up to be able to crawl and walk were so important, as it gave her choices. But talking? Reading? Writing? That wasn’t going to happen. For the most part, I was happy to re-divert my efforts. But you can’t make a decision like that and not have doubts, especially when your working life frequently leads you to encounter slogans like those above. Of course I’d like 100% literacy. Of course I’d like all children to read. I didn’t want to jeopardise the momentum gained by those campaigns. So I didn’t challenge them.

The turning point for those doubts and the beginning of my now very strong urge to challenge them, came at the DSF Conference in Perth in 2019. One of the keynote speakers was Professor Simon Fisher. Professor Fisher is a geneticist and neuroscientist who has pioneered research into the genetic basis of human speech and language. Chloe’s disabilities were the result of a particularly thorough deletion of the short arm of chromosome 5 (Cri du Chat syndrome), so as you can imagine, Professor Fisher’s talk, What Genes can Tell us about the Development of Speech and Language Problems, was of particular interest to me.

I approached him at the conference and asked him, in his experience, did he think all children, no matter their genes, no matter their neurological architecture, could potentially learn to read? He said he didn’t think that. I said I was glad, and told him a little bit about Chloe. He then very graciously explained to me that there have to be certain structures present for reading to take place, and that if they were missing or severely damaged, that reading would be an impossibility. A factual, neurological, biological, scientific impossibility. Not an improbability. Impossible. Not going to happen.

You could call that confirmation bias I suppose. But it was after this conversation that I truly felt I had indeed done the right thing by her.

So when you say “Every child a reader”, you say to me and parents just like me, one of two things:

- Every child a reader but not yours – then why say “every” if you don’t mean every?

- Every child a reader but your child doesn’t qualify as a child – even worse.

There are countless alternative ways to express your keenness to raise standards of literacy instruction and the educational outcomes that follow. There’s a subtle difference between asking for high quality literacy instruction for ALL (like on the cover of my last book) and getting ALL children to read. High quality means knowing who can and who can’t. And knowing why.

Some alternatives:

Instead of every child a reader, why not say: every child a learner?

Instead of 100% literacy, why not say near zero illiteracy?

Instead of all children can read, why not say all children can reach their potential?

I can guarantee you, I am not alone in this. Please listen. When you use those other terms, you hurt people, and I know that’s not what you want to do. So there. I said it. And I do feel better for it.

THANKYou for explaining that so eloquently dear Lyn. I’ve got it. I understand ❤️

Every child a learner. Every child reaching their potential.

Thank you for writing this. Such an important message. ❤️❤️❤️

Bravo, Lyn. And hugs for your pain.

Thank you for saying this so eloquently. It is a phrase I so dislike. I really like the alternative statements that you’ve suggested.

Thank you. Something to think about. I have seen Prof Fisher speaking twice and I know other children that have had gene deletions that didn’t learn to read. Also I have worked with some very severe dyslexics that didn’t learn to read. Not in a functional literate way.

I was speaking to a mum who has desperately been trying to get her children to learn to read for 10 years on Monday. I will share this with her.

Both of my grandchildren have started school with no speech. Both are finding literacy hard to obtain. But that is my family. Its how our gene pool rolls. One has just started. One is in grade 2. One got in the language unit. The other has other obstacles that made entry to the unit void.

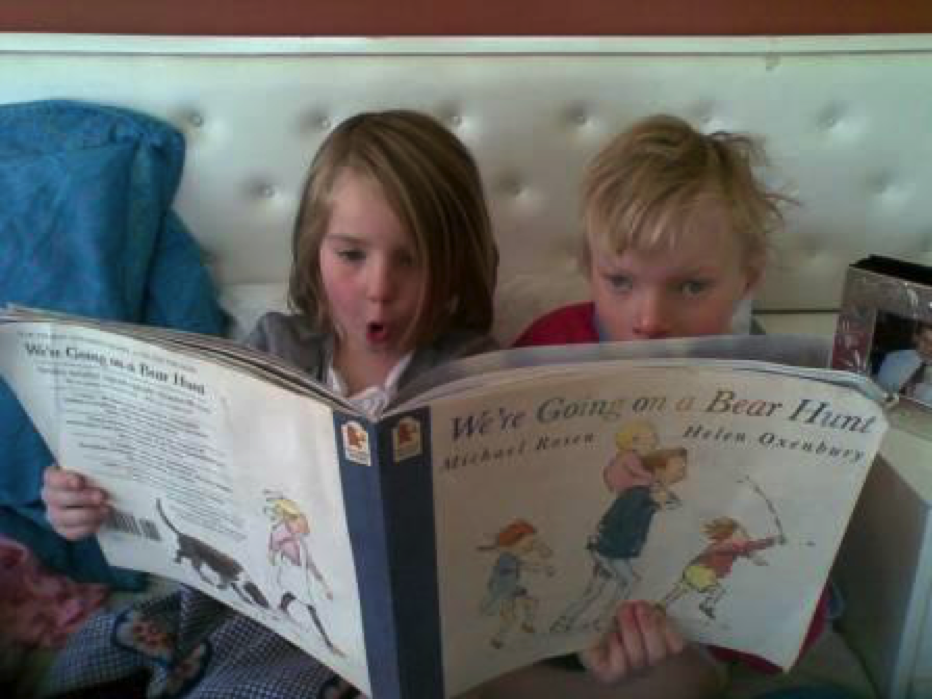

May I ask, did Chloe like being read to?

Both mine love being read to. But they can’t do a whole story so we read till they run off.

Thanks Sandy. Yes, Chloe liked being read to. She had some favourite books too. Bearhunt, as pictured here was one. She also liked Wanda Linda Goes Berserk and The Hippo Hop.

Greater awareness is achieved with this share. Absolutely impossible as it is not natural and to have the doctor validate must have been comforting. Your shares about Chloe are always so heartfelt. Thank you.

I feel for your tender mother’s heart. Thank you for explaining these facts in such a gracious and understandable way. Thank you 🙏