“In real science, one is eventually influenced by the evidence.”

Keith Stanovich (2000)

Once upon a time, it was widely believed that the Earth was flat. Many ancient cultures portrayed the world as being a flat surface and this belief survived until Pythagoras and the like started proving otherwise in the 6thcentury BC.

Through the cumulative efforts of cosmologists, philosophers, mathematicians and astronomers, to name but a few, a vast body of knowledge about the shape of the Earth has developed. The competing view has taken something of a back seat due to the sheer weight of evidence against it.

There is however, even in this day and age, a group of people who cling dogmatically to the flat Earth ideal and they are called, surprisingly enough, Flat Earthers. Many are influenced by religious literalism and strong suspicion of the government, and most are mocked or ignored by the rest of the world.

If only the science of reading had similar clear divisions between itself and what has come to be a pseudoscience of reading. Reading science doesn’t lack a weight of evidence, and yet false theories continue to exist.

Flat Earthers do very little harm, although indoctrinating children is somewhat abusive, especially if that indoctrination causes them to reject science. Pseudoscience in reading, however, has racked up an extensive list of casualties, not least an incarcerated/disenfranchised underclass in every English speaking country.

A Brief History of Reading Science

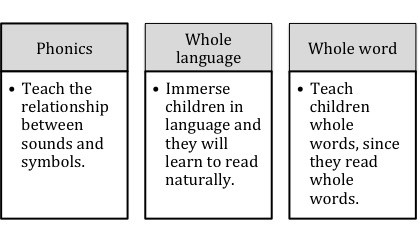

Back in the old days, when functional brain scans and the internet didn’t exist, three major theories about how children learn to read emerged. These were known broadly as phonics, whole language and whole word.

Phonics can be regarded as a bottom-up approach, starting with the smallest units, i.e. letters and sounds, and building up towards words, phrases and sentences. Whole language and whole word are top-down approaches, in that they start with larger units such as meaning and whole words, and work their way down to the smaller building blocks of language incidentally, if at all.

Scientists in numerous fields have spent the best part of the last century testing the theories. Some started off supporting one theory, and found that they had to change their mind about their notions of learning to read.

Keith Stanovich talks about this in his highly acclaimed book Progress in Understanding Reading: Scientific Foundations and New Frontiers. He says:

“We did start out with a theoretical bias, one consistent with the top-down view. But in real science one is eventually influenced by the evidence, regardless of one’s initial bias, and the consistency of our findings finally led us away from the top-down view.”

This kind of hypothesis-testing is how we concluded that he brain was, in fact, not the organ we pushed blood around our bodies with. It’s how we found out that the heart wasn’t the seat of thought. It’s how we came up with useful ideas that stuck, like hand-washing before and after performing surgery.

The act of testing is called research. The result of testing is called evidence. These are very important terms to understand when selecting teaching methods. The words research and evidence are thrown around a little too much in the education arena without being properly defined.

Testing and re-testing, over time, by different scientists and coming up with predictable results produces a theory. When various scientists agree on a theory, we have what is called scientific consensus. When scientists from various fields come to the similar conclusions, this is known as convergence. Psychologists, linguists, educators and speech-language professionals have done so on the subject of reading.

A century of testing and evaluating evidence has resulted in a consensus and a convergent understanding of the processes involved in achieving skilled reading and writing. Here is the conclusion:

- Systematic synthetic phonics is currently the most effective method of initial reading instruction.

- Systematic synthetic phonics is a necessary step in the process of literacy acquisition, but is not sufficient on its own to guarantee literacy for all.

- Timely and appropriate instruction in phonological awareness, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension is also necessary to ensure literacy for the largest possible population.

- Reading is not a psycholinguistic guessing game.

- Learning to read an alphabetic language by memorising whole words in the absence of blending and segmenting their parts is ultimately impossible for most people.

The problem is, claims that children can learn to read using context and whole words, like the claim that the Earth is flat, are not so absurd that anyone can dismiss them out of hand. There are enough instances of children learning to read in spite of poor instruction and there are enough examples of the Earth being seemingly flat to give these theories some weight.

Why are Whole Language and Whole Word Methods Like the Flat Earth?

Whole language and whole word are very seductive theories, and still enjoy enormous popularity worldwide. They tie in with the trendy, but ultimately empty idea that children’s creativity, personal interests and individual sparkle should be at the forefront of all teaching.

Now I’m all for individualistic and sparkly children, but nothing loses a sparkle quicker than a child entering their third year of schooling still unable to read/write/count. No one enters my practice to get help with their creativity, collaborative abilities, critical thinking or play-based skills. They want to learn to read, write and count as a result of not being well taught at school.

The casualties of top-down ideas are everywhere. The remnants of whole language are deeply and firmly entrenched in the collective educational psyche.

Words are not independent objects to be learned by sight like people’s faces or the flags of the world’s nations. They contain a limited set of parts that can be combined and recombined to form many and varied wholes.

Methods which ignore this truth have been shown repeatedly to be less effective, but, like the flat Earth theory, they don’t seem to go away.

Maybe it has something to do with the fact that when whole language and whole word started to gain popularity, like the Flat Earthers, their proponents didn’t have the research to verify their claims, but either did anyone else.

And so the three camps became ever more distinct from one another and rivalry, bitterness and vitriol ensued. But there’s one very important point that often gets missed, and that is that whole language and whole word proponents failed to advance their theories. Most of their time was spent furiously defending their position or trying to merge with the other two.

Not so the majority of phonics proponents. Theorists, researchers and practitioners in this field continued to refine and build upon phonics. They realised that phonics is necessary but not sufficient for fluent reading with comprehension.

The most effective practitioners use appropriate and timely instruction in the keys to literacy. Systematic synthetic phonics should feature most heavily within the framework of those keys, especially in the early years. This is widely acknowledged by authors, publishers and teachers who understand the evidence base. But more has to be done to get children reading and writing competently.

One of the greatest problems faced by people who understand this is that there is no standard name for this set of principles. They are denigrated by whole language and whole word proponents, despite vindication by science. Their work is referred to only as ‘phonics’. I myself have even been, hilariously, accused of being a ‘phonicator’ or ‘phombie’ for supporting and advancing the notion that systematic synthetic phonics is important.

Name-calling and misrepresentation of this set of principles implies that those who support systematic synthetic phonics are basing their stance on philosophy. Therefore, if it’s philosophical, the competing view must be equally valid. Research evidence is ignored.

A further problem emerges because reading scientists are just that: scientists. They tend not to use their energy to create user-friendly explanations of complex processes. They are generally busy conducting and publishing actual research. So we have a vacuum, and into that vacuum creeps the philosophical brigade, whose time isn’t spent in the lab, and so they are free to spread disinformation in order to cling to comforting falsehoods.

A grudging recognition of the importance of phonics has started to seep into some corners of education and a new beast has arrived on the scene called balanced literacy. It is touted as a mixture of low-pace, analytic phonics, whole language and whole word; the worst of all possible worlds, in fact.

Top-down proponents say that children should be taught to read using the following strategies:

- Being read to

- Guessing at unknown words

- Using context to guess unknown words

- Using picture cues to guess unknown words

- Learning ‘sight words’ by memorizing their shape or visual features

- Looking at the first letter of a word and moving to the next word (this is the balanced phonics part)

These methods fail to serve a large number of children and have indeed been shown in laboratory conditions to be the strategies employed by poor readers who have not yet mastered the alphabetic code.

Yet balanced literacy and whole word proponents maintain an illogical attachment to these methods instead of advancing the field by admitting they were wrong. To admit that would be painful and challenging. It would require the author/teacher to face that they have made a mistake that has likely done a disservice to many children.

Top-down methods sound plausible and are often strongly argued. Politicians, education bureaucrats and the general public do not, and often cannot, understand the data put forth in the research. Therefore they are swayed by the most emotive, strongest argument.

Unfortunately, whole language, and to a lesser degree, whole word proponents are far more advanced and well organized than Flat Earthers. We would laugh them out of the geography lecture theatre if they tried to put their views forward in a tertiary setting. And yet I don’t hear anyone laughing at teacher training colleges when the psycholinguistic guessing games or sight word lists spring up.

If you are a teacher or a teacher in training, your acceptance of flat Earth reading theory could make the difference between literacy and illiteracy for countless children. This open letter to student teachers might provide some insight as to how to demand better training.

References

Stanovich, K.E. (2000). Progress in Understanding Reading: Scientific foundations and new frontiers. New York: Guilford.

Hi Lyn,

What an excellent chapter. I’m really looking forward to the publication of your book and reading it! In the meantime, I’ve added your borrowed chapter to the thread devoted to the ‘phonics debate’ at the International Foundation for Effective Reading Instruction here:

http://www.iferi.org/iferi_forum/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=1044&p=2137#p2137

Best wishes,

Debbie

Thank you, Debbie. That’s very kind. I’ll head on over to that and the other fantastic threads on your forum!

Cheers,

Lyn

How do I “Like” or “Love” this post? 🙂

Thanks Ken! Like or love it by sharing it! 🙂

This post is excellent. I will be ordering your book when it comes out. Thank you for writing articles like this. It has been posted on my facebook page “Northern California Reading Teacher’s Network” a page devoted to information about the science of reading.

Thanks Jeanette!

I’ve liked and followed your Facebook page – fantastic resource!

Lyn