If parental input is driving your system’s success, there’s something wrong with your system

Chilli was a 9 year old boy who couldn’t read or write. He’d been issued with the same type of take-home readers and magic ‘sight word’ list that everyone else in his class had been issued with, year in, year out, but after four years of formal schooling, he was very, very behind his peers.

He had qualified for some funding to help boost his literacy and that’s how we came into contact. He had actually been given literacy intervention prior to my being called up for the job, but it was Reading Recovery and therefore resulted in no sustained progress.

He was a witty, charming, happy-go-lucky kid and I knew we’d get on just fine, but it became clear in our first lesson that he was having trouble maintaining focus. We were doing some basic spelling of words containing newly introduced graphemes. I gently said, “Chilli, I need you to try to answer my questions and look at the words. You keep changing the subject and looking away, but we’ve got quite a bit to get through before the lesson ends. Would you mind just keeping your attention on this for now?”

He apologised and said, “I’m really hungry. I’m thinking about getting something to eat.”

“Oh, did you forget to have breakfast?” I asked him innocently.

“I didn’t eat breakfast,” he murmured. “Why not? Did you forget?” I asked.

His face fell into an uncharacteristic frown, “My mum’s boyfriend gets really angry if we make any noise in the morning.”

I gave him my muesli bar and made a note to talk to the school about possibly providing some food for him when he came in. The principal told me that Chilli’s case was not rare, and that there was a breakfast club at the school that provided food before the day started, but that Chilli was often late and missed it.

There was another child from that school who qualified for tutor funding; a slight, pale blonde girl with big glasses. We’ll call her Tamara. Unlike Chilli, Tamara was quite withdrawn and although she did get breakfast at home, she often came to me tired and unsmiling. It turned out that she was missing her father, who was in prison, and she wasn’t sure when he was coming back. Sometimes she’d get to visit him on the weekend, but not often, as prison was very far away and her mother didn’t drive.

I was young and naïve back then and being a private tutor, I hadn’t really encountered many children whose home lives were this far from ideal. But I was meeting them now and helping them to read and write. What struck me most was that there was an unspoken resignation on the school’s part that those children who didn’t have caregivers available to do the literacy (and probably numeracy) homework set by the school, would inevitably fail and that there wasn’t much to be done about this, especially if private tutoring were out of the question.

A significant portion of this school’s student progress was being outsourced to parents and caregivers. If none were available, it was too bad.

Many of the public spaces in the school contained posters extolling the virtues of home-reading. Slogans like “Reading is taught on the lap of a loved one”, or containing “joy of reading” being somehow caught were pasted on all the walls.

The walls also displayed names of children and the words they had memorised, split into colourful sections. In every room there were several outliers who languished at the very beginning of those lists. I had no doubt that Chilli and Tamara were among them, and probably had been for years. How was this acceptable?

I looked at the levelled book boxes and wondered how it must feel to always have to choose from the same, stultifying, overly repetitive, simplistic bottom ones year after year. And what it must be like to take your book home to never have it so much as retrieved from your bag, your reading diary left empty while your peers whizzed by, collecting stickers for their nights of reading and getting certificates from the principal.

How painful must be the ignominy of the weekly spelling test, where unlooked-at words delivered on Monday were humiliatingly scratched out on Friday, to be marked and returned with 0/20.

So the Chillis and the Tamaras of this world, already suffering immeasurable disadvantage with chaotic, hostile home lives devoid of parental input, also had to cope with teachers who didn’t have to tools to teach in spite of that, and more often than not, the reprimand for not having done their homework.

This is what cycles of poverty look like. This is where preventable entry into the criminal justice system has its beginning. And it doesn’t have to. Schools can equip their teachers to teach reading and writing regardless of home life. In fact, that is one of the non negotiable duties of a primary school.

I applaud schools that attempt to provide food for its hungry students, but it amounts to very little if the educational diet isn’t also nutritious. My advice is this: If you have a student who is not progressing in literacy because they don’t do their homework, you are missing a tool. That tool will vary, depending on what you already do, but home support cannot, in any way, be part of the picture if social justice is important to you.

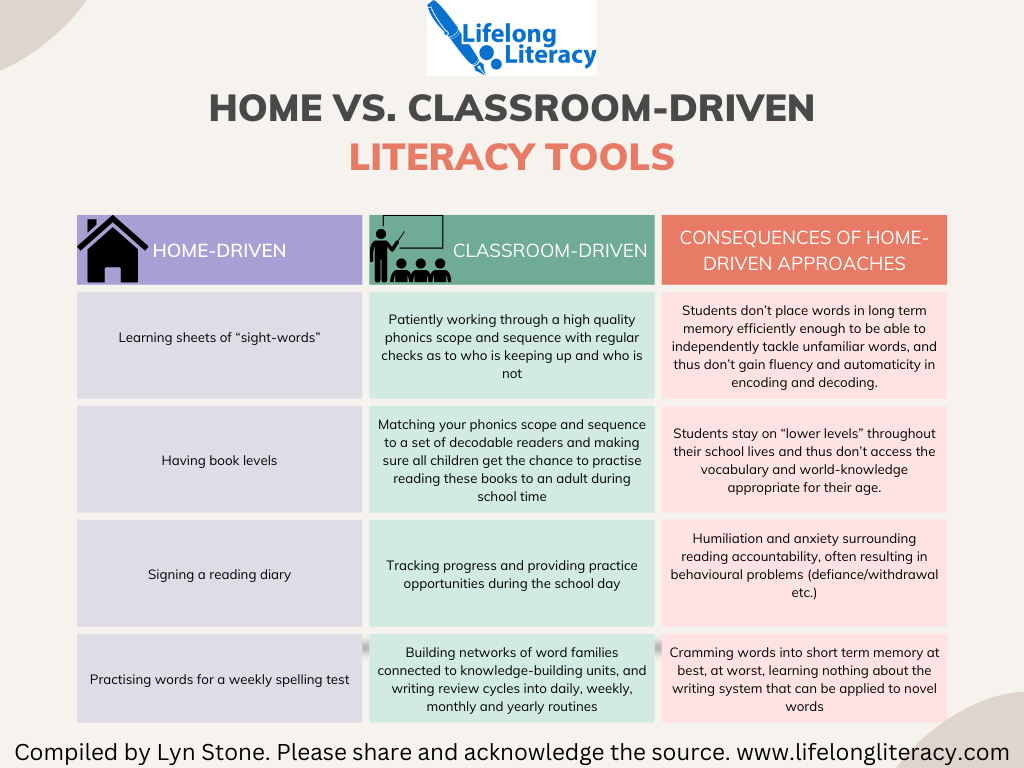

The table below sets out the difference between home and classroom-driven approaches and the consequences of schools not taking 100% responsibility for their students’ literacy.

Don’t get me wrong: It’s lovely when parents work alongside schools to facilitate the journey to literacy, and I encourage the recruitment of keen parents to help out in this way. But it simply cannot be one of the make or break factors. We have to inoculate our students against circumstances not ideal for literacy acquisition. Approaches that are in some way reliant on home life only perpetuate social disadvantage.

Here here Lyn. As a private tutor, I have just been approached by the grandmother of 4 Chillis/Tamaras – a whole family of kids who are instruction casualties. What galls me is that the older ones feel like complete failures when in fact the schools have actually failed them. Where are their progress charts, list of learnings, KPIs? And what are their consequences when kids graduate illiterate or subliterate? Now a whole family in a small SES town has to fund private tuition times four.

It’s a travesty for sure. There is so much work to be done to reverse that kind of damage!

This institutional/structural failure blames the individual/family seems like a very common obfuscation defence these days – obesity, poverty, political apathy.

All of these things are issues in their own right for sure, but what we can and should focus on are the things that we as educators can change!