As a teenager, I was a regular visitor to Tripoli in Libya. My father was the British Consul there for around four years and being at boarding school, I went and stayed with him during my holidays.

One year, it just so happened that hostilities between the USA and Libya were increasing, and many of the world’s news agencies sent their journalists over to cover the story. Part of my father’s job was to speak to those journalists, and he often hosted them at the British Residence on official business. He would also entertain them there, and help them rest and recuperate from a sometimes harrowing job.

I consider myself fortunate to have spent time in such good company. They were mostly intelligent, hardworking, adventurous, hilarious people, and they made a deep impression on me. Three stood out: Marie Colvin, David Blundy and Charlie Glass.

Marie was every bit as heroic as her various biographies made out. She was one of the only journalists that Gaddafi would speak to after his compound was bombed. She reported on him truthfully and even when she was less than complimentary (because let’s face it, Gaddafi wasn’t exactly loveable), he still granted her an audience. Her absence of ego and determination to get to the truth were apparent in everything she did. I was in awe of her. She was murdered in Syria in 2012.

David, or “Blunderbuss” as he was fondly known, was as funny as he was intelligent. His playful sense of humour was often on display both in his writing and in his personal life. Once, when playing tennis with my father, a wayward serve struck him. He staggered theatrically and cried out, “I am hit!” to the laughter of everyone present. He was killed by a sniper’s bullet in El Salvador in 1989.

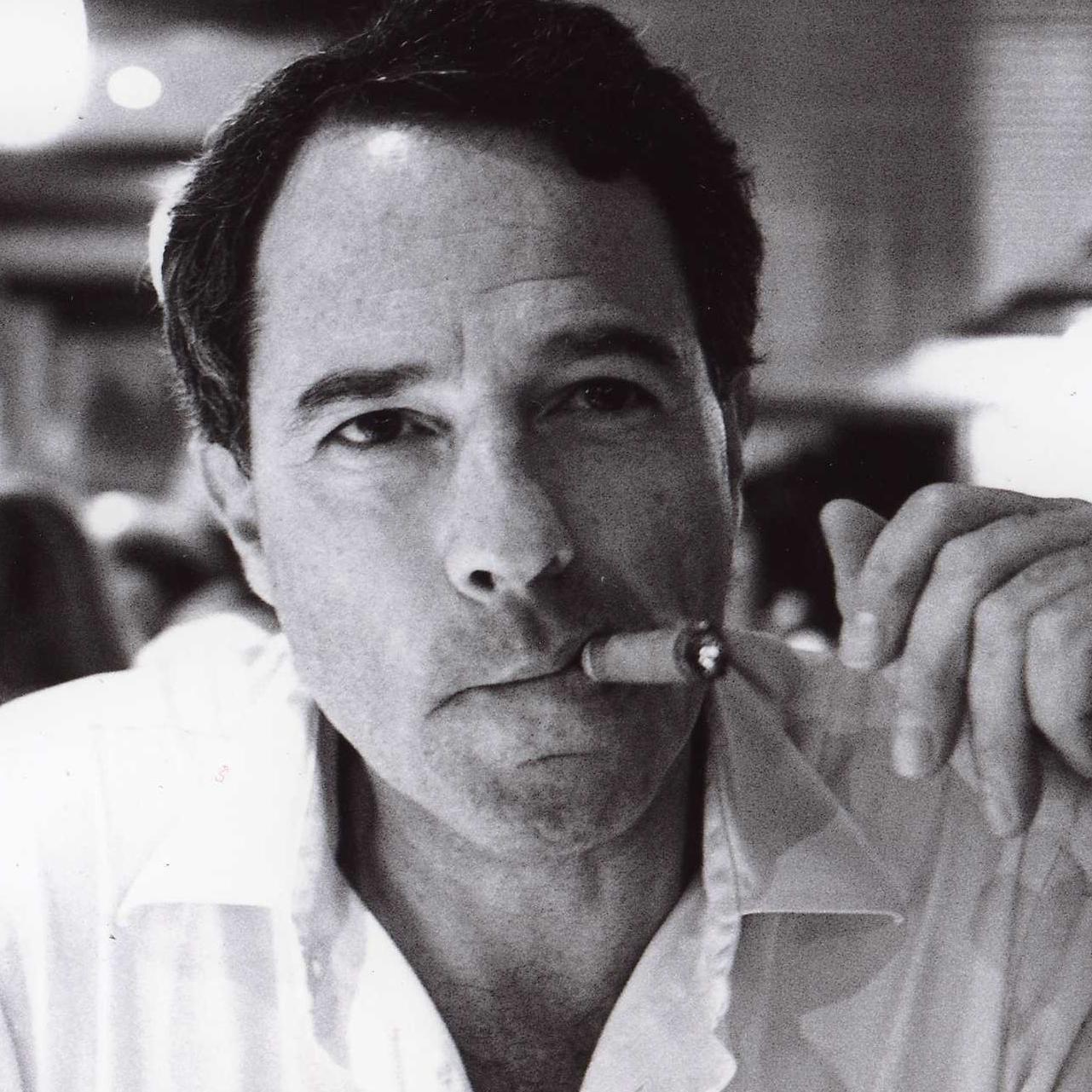

Charlie Glass was softly spoken but his authority was unmistakeable. I loved to sit and listen while he and my father talked. He was kidnapped and held hostage in Lebanon in 1987, but escaped his captors after 62 days. He was an acknowledged expert on Middle Eastern politics and reported from that area in numerous articles, books, and an incisive blog that I read to this day.

I’m no biographer, but I did have some insight into what drove these people, and aside from a love of adventure, they were mainly motivated by truth and compassion. They placed themselves in danger so that they could tell the stories of the people on the front lines. These reporters were undoubtedly gifted, highly courageous, and able to synthesise many diverse strands of a political landscape so that others could understand complex situations.

They were hated by many for bearing witness. Their opponents were those who either profited from an untenable status quo, or who stood to profit from their enemies’ defeat. Marie, David, Charlie, and their ilk were not hated for lying or distorting facts or hiding the truth, because that’s not what they did. They were not hated for being inaccurate, because that’s now what they were. Corrupt leaders could only try to claim that these journalists had bias, or weren’t qualified to comment, or in the pay of some shadowy organisation, or were somehow profiting from their reporting. What they were really doing was revealing inconvenient, uncomfortable truths.

I am lucky to have known them. They influenced my career as a writer and shaped my desire to report the realities of conflict in my own field. It is with disappointment then, but familiar resignation, that I see criticism of the journalist Emily Hanford and many others when they do their job and bear witness to the state of literacy instruction in the 21st century. I’ve seen this sort of behaviour before. It always comes from wrongdoers. Feeling the eyes of the world on their systems, behaviour, vested interests, and beliefs, they attempt to shoot the messenger. It’s a typical, desperate move to deflect scrutiny and silence opposition.

So the next time you hear the term “reporter” or “journalist” used as some kind of veiled insult, do pause and reflect on what that really means. That insight alone is worth a thousand words.

test

test2